Report

Waste Stream Mapping: Overview and Concepts

Written by Victoria Frausin

Overview

“Water and air, the two essential fluids on which all life depends, have become global garbage cans.” - Jacques Yves Cousteau

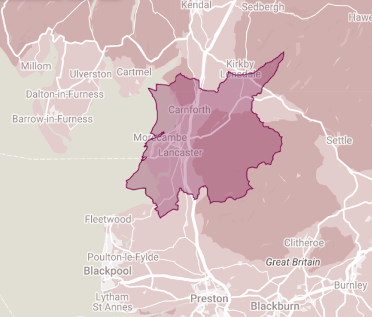

Lancaster District

A local government district of Lancashire, England. It covers the city of Lancaster, the towns of Morecambe, Heysham, and Carnforth, as well as outlying villages, farms and rural hinterland. It covers an area of 567 km2, with a population of 142,934, making it 0.3% of England’s total population.

According to the 2020-2021 report by The Waste and Resources Action

Programme (WRAP), Lancaster’s performance is below the national average (see diagram 1).

For every ton of waste produced by consumers (post-consumption), 20 tons of waste is produced in the extraction process alone” (Meadows and Randers, 2004). Although more attention is paid to Municipal Solid Waste, more waste is generated at the extraction and production than in the post-consumer stage.

But, what is waste?

Waste hierarchy

At the top is elimination of waste. This could be through campaigns to stop unnecessary

packaging, or the production of disposable electronics for instance. Reduce and reuse are also

in the top layers. It is these top three green layers where most focus should be when it comes to transformative solutions. However much of the focus on waste management focussed on the lower three segments. Recycling is preferable to recovery (the process of reclaiming or reusing materials or energy from waste that would otherwise be discarded) and disposal, which refers to landfill, waterways/ocean dumping (e.g. untreated sewage), export, littering and fly-tipping.

However, recycling is not an eternal circular material flow. It is a waste producer industry that involves transport, virgin materials and energy loss. Whatever waste is recycled will almost certainly – and typically after only one recycle – turn into waste that will be transported to a landfill or incinerator.

Waste infrastructure – who and what goes into managing waste:

- Peoples’ time whether paid or unpaid

- Fleets of collection vehicles

- Waste transfer stations

- Materials recovery facilities

- Technologies that attend to residual waste Incineration with/without energy recovery

- MBT (mechanical/biological treatment) plants

- Landfills

- More virgin materials to mix with materials – particularly plastics

How waste is measured

The unit of measurement for waste can vary depending on the type of waste being measured. For example, in the UK liquid waste is measured in metric units such as millilitres or litres, solid waste is measured in metric units such as tonne and greenhouse gas emissions are usually measured in metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e).

Collection of data

“A system of accounting that can’t count what matters.” - Rebecca Solnit

The challenges

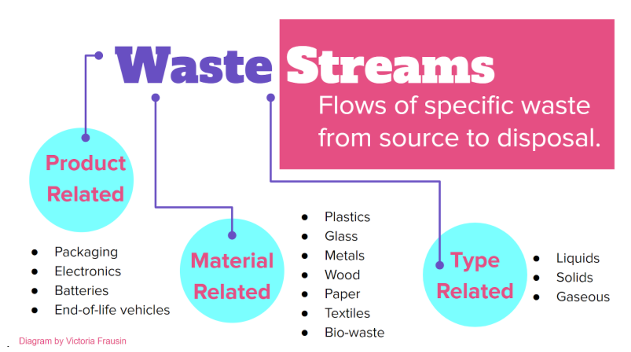

What are waste streams?

As well as the definition of waste, there is not an agreement on what “source to disposal” means. Source as the place where it came from can be interpreted as wide as the original source (water, soil, nature for example) to the supplier (shop, company and so on). Disposal could be understood as water, air or soil (nature) to the bin to be collected by the waste company.