Waste 101

What is waste?

At first this seems like a simple question – think of ‘waste’ and you probably think of the things we put in the bin on a regular basis. The plastic cereal bar wrapper, the T shirt with the hole in it, the broken charge cable and those spaghetti bolognese leftovers that now seem less than appetising are all likely candidates for the bin on the basis that they’re something that’s no longer needed, wanted or useful.

What’s in your bin? Walk over and take a look right now – what do you find?

While every bin is unique, there are also certain similarities that add up to a bigger picture. For starters, most people have their own equivalents of the wrapper, the T shirt, the charge cable and the spag bol. That’s why, every year in the UK, we throw away 1.7 billion pieces of plastic packaging, 300,000 tonnes of textiles, 400,000 tonnes of e-waste and 6.42 million tonnes of food from households.

Seems like a lot, right? It does, but here’s the thing: up until now we’ve just been talking about the rubbish that we SEE. That is, those things that we personally put into the bin on a regular basis. But, when we’re talking about overall quantities of waste, the truth is that most of the waste on the planet is the stuff that we DON’T see because it never actually passes through our hands.

In fact, it isn’t generated in our homes at all because it comes from the manufacturing process.

The sneaky waste that you never get to see…

See, here’s the thing: Even if household waste was miraculously reduced to zero overnight, we’d still have a waste problem. Because the majority of waste produced in the world isn’t generated in the home at all.

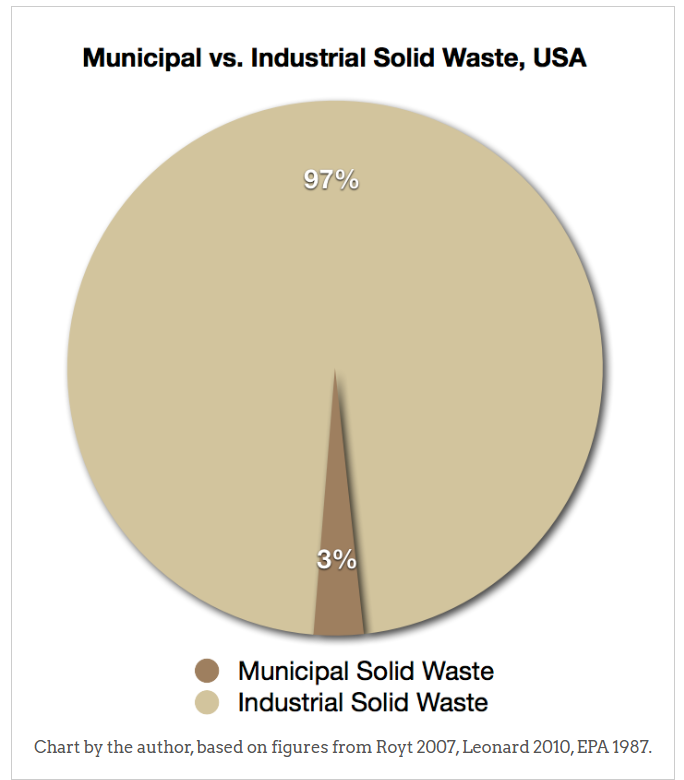

Take a look at the diagram below which is based on figures from the USA.

As you can see household waste is only a tiny fraction of the overall waste problem. Instead, a whopping 97% of waste is classed as ‘industrial waste’ – that is, waste that’s involved in the production of things.

Now, in reality this figure is much debated because accurate reporting of industrial waste is very hard to come by. This is partly due to commercial confidentiality agreements and a lack of an agreed definition of what constitutes waste. For example, most reported figures don’t include waste that is generated through the process of mining and extracting raw materials. Nor do they include the amount of wastewater that is generated in the manufacturing process, since most figures only account for SOLID wastes.

This is a problem as, if something can’t be measured and reported accurately, it’s very hard to take action on it. The fact that we currently know much more about the volume and composition of household waste means that it often becomes the target of waste reduction efforts.

And, while it’s great to encourage recycling at the household level, the problem is this is only addressing a small fraction of the bigger waste picture since, despite the uncertainties in the data, it’s still clear that manufacturing waste is a MUCH bigger contributor than household waste.

Most of us have grown up thinking that the waste problem is caused by us throwing things away and that better household waste recycling is the ultimate solution to our waste problems, so it can feel strange to learn that this is not, in fact, the case.

The truth is that recycling DOES have an important part to play in reducing waste. But, in reality, it’s more of a ‘best supporting actor’ rather than the starring role.

If industrial waste is such a big contributor to the global waste mountain, why don’t we hear more about it?

“If it can’t be reused, recycled, and composted, it should not be made.”

– From Derrick Jensen and Aric McBay’s 2011 book What We Leave Behind

We’re so used to thinking of waste as a post consumer problem that it can be really shocking to hear that the scale of household waste pales in comparison to the volume of industrial waste produced in the world. But there’s actually a good reason for the silence here. Here are 4 reasons why we don’t hear as much about this problem as we should do:

- There is no commonly agreed definition of waste across or within countries, meaning that what counts as waste in one place may not be considered as such elsewhere.

- Industrial, construction, demolition and excavation waste are protected by commercial confidentiality arrangements, making it impossible to know how much waste different companies are actually producing.

- Waste generated by transportation is not accounted for in the statistics, despite the fact that we live in a culture that relies on the long distance of transport of people, raw materials, finished products and waste itself.

- A focus on industrial waste would require a major reframe in how we think about – and try to tackle – global waste issues. Taking industrial waste seriously would mean the onus would be on companies to adopt genuine zero waste and circular design and manufacturing approaches so that products are designed to last longer and components are made to be recovered and used again. This would lead to economies based on reuse and repair rather than the constant purchase, use and discard of new items. Work on regenerative and circular economies shows this is both exciting and eminently do-able, and this is EXACTLY the kind of change that Ref/use Lab would like to see happening. But it definitely requires a more fundamental change to how we currently live and work. This is why it often feels easier to stick to the old narrative that waste is a problem generated by householders that can be solved with better recycling systems, even though this isn’t actually true!

But I thought recycling was the solution! What’s going on here?

Yes, recycling can be very helpful in tackling some forms of waste, some of the time. But the truth is that, most of the time, there are other, more effective approaches that we should be trying first! Why? Meet the waste hierarchy, a handy tool that helps us understand the big picture of waste.

New to waste hierarchy? Don’t worry, it’s simple. It lists the order and importance that should be attached to different waste management options if we’re serious about tackling trash once and for all. The idea being that, if we want our actions to have maximum effectiveness, then we need to start with the approaches at the top of the hierarchy and work our way down ONLY when we have exhausted the other options available to us.

There are many different versions of the waste hierarchy out there with more specific versions being produced for different waste streams. However, at their core, all of them revolve around the simplest and most commonly known version, which is Reduce, Reuse, Recycle. Many of us will have grown up being taught these three R’s in school as a memorable phrase which rolls off the tongue easily. But, in reducing it to a slogan, we’ve lost a very important aspect, which is the priority that should be attached to each element. Because Reduce, Reuse and Recycle aren’t equal. They are ranked in order for a reason.

Due to the large amount of resources used to manufacture an item, the most effective way of dealing with waste is to stop it from happening in the first place. That’s why prevention and reduction will always sit at the top of the waste hierarchy.

Let’s imagine you’re out and about for the day and you want to grab a coffee. The best option will always be to use a cup that can be washed and used again many, many times since no waste is produced until that cup finally breaks – at which point it can hopefully be recycled. This is what PREVENTION looks like.

What if you don’t have a cup with you? Your next best option is REUSE – that could look like repurposing your takeaway cup into a plant pot, desktop organiser, or kids’ craft activity. Reuse is very fashionable at the moment with thousands of creative upcycling projects popping up on Instagram and Pinterest. But Reuse comes second place in the waste hierarchy because there are limits to what it can achieve. Let’s be real: there’s only so many plant pots, desk organisers and kids’ crafts one person needs so, if this is your go-to option for coffee, you’ll need to start binning them sooner or later.

Can’t reduce or reuse? Then by all means recycle that coffee cup. It’s better than binning, but it’s also the third place option for a reason. Each time something is recycled, it has to be collected, transported to the depot, sorted, baled, shipped to the processing plant and then remodelled into something else. That takes a lot of energy that we don’t get back. There are also limits to what can be recycled. Takeaway coffee cups are often made of a mix of materials, which makes it harder to recycle them. Finally, despite all those energy inputs, recycling often results in an inferior quality product. For example, plastics can only be recycled a certain number of times because they will begin to degrade with heating and reheating to reshape them.

The point of this discussion isn’t to demonise recycling and upcycling because both have an important role to play in reducing waste. (Please DO use your recycling bins and DO get creative with your reuse and upcycling!) But let’s also use the waste hierarchy to get real: any serious attempt to address waste has to start with prioritising prevention and reduction as a matter of urgency.

Why is recycling promoted over other options?

Look around you in daily life and you’ll see there’s no shortage of publicity around reuse or recycling. For example:

- Recycling credentials are often promoted in connection with new products – e.g. clothing labels boasting “This garment is recycled!” or the water bottle that says it’s made with recycled stainless steel.

- A whole industry has developed around reuse – e.g. reuseable cups and bags for life.

- Public information campaigns promoting recycling – e.g. recycling ads on the side of bin lorries.

- Recycling taking place in store – e.g. H&M’s garment collection program where you can donate old clothes in exchange for a voucher.

- Charity recycling schemes – e.g. those bin bags that come through your door asking for your clothes in exchange for charity

- Companies promoting ‘green’ initiatives for dealing with waste – e.g. supermarkets giving unsold food to food clubs or councils generating energy through anaerobic digestion or energy from waste schemes.

But there’s almost nothing promoting prevention, which is by far the most effective approach to dealing with waste! This makes no sense. Imagine you accidentally left a tap on and came back to find your bathtub flooding. Surely you’d turn off the tap before trying to mop up the floor? Yet, when it comes to waste, we do the opposite again and again. Promoting reuse and recycling over prevention and reduction looks like trying to mop up the floor without turning off the tap!

So why the relentless focus on recycling? Let’s go back to our list and imagine what the prevention alternatives would actually look like:

- Rather than recycling being promoted as a way to sell new products, prevention looks like “do you really need to buy this?” – Patagonia are a rare example of a company that did this with their ‘Don’t Buy This Jacket’ ad campaign.

- Rather than a whole industry developing around reuse, prevention looks like “Nice bag, but why not use one you already have? Or at least buy second hand or get it on Freegle?”

- Rather than public information campaigns promoting recycling, we could be promoting activities that might actually result in waste prevention like repair services, clothing swaps and hire schemes.

- Rather than bringing recycling in store and using it to incentivise the purchase of new items, prevention looks like retail outlets offering clothing swap parties and repair services.

- Rather than supermarkets focusing on donating unsold food, prevention looks like implementing supply chain policies that minimise waste in the first place and working hard to build a fairer food system where are people don’t need to depend on surplus food in order to get by.

What do all these alternatives have in common? They are not based on selling new stuff. In fact, they are actively discouraging it.

Prevention is unpalatable to the bigger brands and manufacturers who currently dominate the global economy because their business model revolves around a “take, make, discard” system, where materials are extracted from nature to produce goods that are consumed quickly and then discarded, leading to constant sales of new stuff.

If we took prevention seriously, sales of new products would fall, meaning that those business models would have to change.

In contrast, recycling is more appealing to these businesses as it holds the (false) promise that sales of new goods can continue unabated, leaving those business models – and the profit margins that underpin them – intact. Unlike prevention, recycling suggests that nothing needs to change. Even worse, recycling can and is being used to justify and promote even more purchases (“buy this thing to help the environment!”, “use your waste to help the poor!”, “donate your old clothes here and get a discount off a new purchase!”). That’s why so much attention goes into mopping up the floor when we need to be turning off the tap.